The Cut-Out Girl, Maus, and Second-Hand Holocaust Narratives

Please note that this post contains an illustration from the graphic novel, Maus, which you may find upsetting.

The Cut-Out Girl is part Holocaust biography, part modern-day memoir. Full of unanswered questions about his family's past, author Bart Van Es looks into the story of his Jewish aunt Lien, who was adopted into his Dutch family after World War 2, and then disowned decades later.

It’s both a personal family narrative, and a general look at the Netherlands' approach to Jewish people during the war. It's simultaneously detached and personal, since the author is technically Lien's nephew, but has never met her before he begins his research. The book interweaves the past and the present, telling both what happened in Lien in the 1930s, 40s and beyond, and the author's modern day experience reconnecting with Lien, interviewing her, and researching her story.

As Lien tells van Es, and van Es tells us, Lien was a happy girl living in a non-observing Jewish family in The Hague when the Nazis invaded. In 1942, her parents sent her to live with a family of strangers for a few months, in order to keep her safe. She never saw them again.

The Cut Out Girl’s real strength is in how it tells more untold, unconsidered stories. It speaks of what happened to children, unlike Anne Frank, who went into hiding separately from their parents, in order to keep them safe, and became orphaned in the process. It explores the instability of constantly moving and hiding, and the potential for abuse inherent in the fact that these children are ‘cut out’ of their families and pasted into new ones. It explores how just because someone took in a Jewish child, that didn't mean they were altruistic or doing it for good reasons — even though of course it also involved great risk, and so was laudable in that way. It explores the isolation of being a Jew in hiding, with Lien not realising that her own next door neighbors were also harbouring a Jewish girl.

And it explores the trauma after the war. I feel like many WW2 stories end in one of two ways — in death, or in surviving to the end of the war. But the book highlights the experiences of Jewish people trying to return to the Netherlands after the war — some kept in camps, along with the newly detained Fascists, for months, some stuck across Europe as no transport was sent to help them return, most with no homes to return to and a government that did not want to help them. The book explores what happens when war is over, and life is safe again, but a girl’s family are still all dead. And it explores what happens when a girl feels that one place is her family, but that place may not necessarily feel the same.

It reminds me of Maus, a tour de force of a graphic novel that won the Pulitzer prize in 1992, that also blended historical retelling with present day personal struggles. In Maus, comic artist Art Spiegelman interviews his father about his life in Poland during the rise of the Nazis and during the war, while also exploring his own difficult relationship with his father in the present day. It's not just a graphic novel about the Holocaust; it's a graphic novel about writing a graphic novel about the Holocaust.

Maus, like The Cut Out Girl, does not provide any easy answers. The story that Spiegelmen tells is bone-chilling, but he also presents his father in the present day as selfish, miserly and racist. Sometimes, Spiegelman wonders whether this horrifying past helps explains why his father is the way he is, or whether that is simply his father's personality, regardless of what happened.

But unlike The Cut Out Girl, Maus was published serially over 11 years, and so gained tremendous success while still being written. Spiegelman is incredibly aware of the fact that he is profiting off his father's story, and the story of all European Jews, even as he continues to research and draw. He is telling a narrative that isn't his, and getting praise and awards for it, and his growing moral discomfort plays a significant role in later sections of the book.

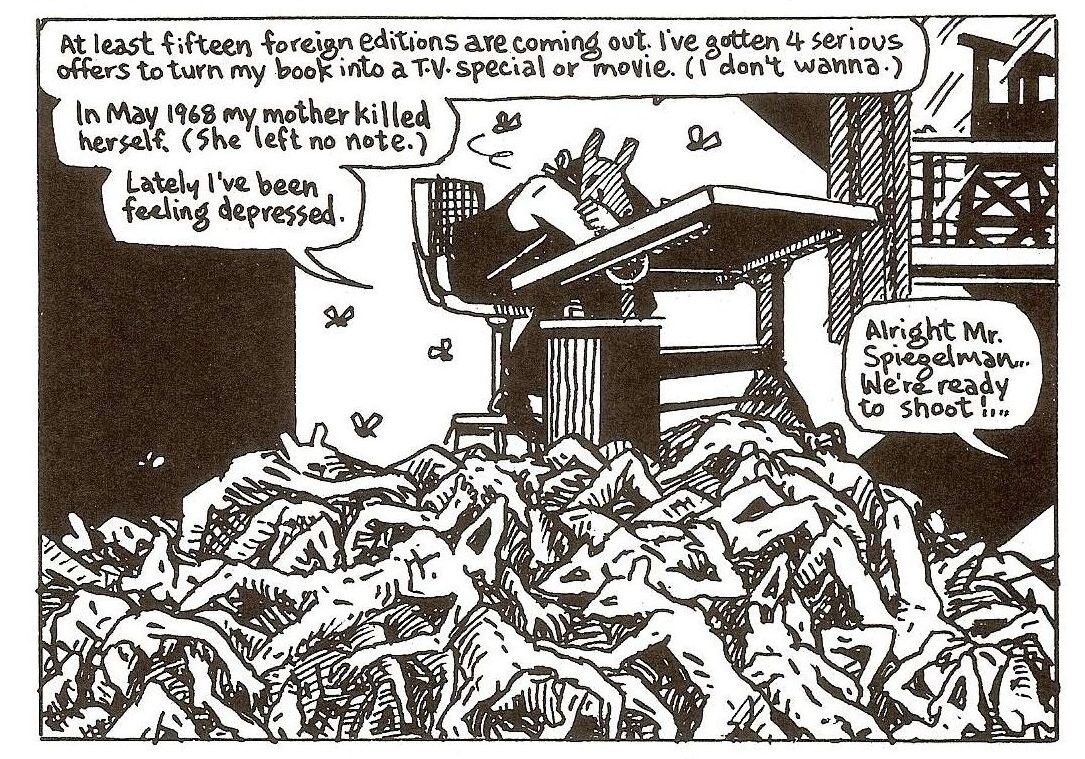

Throughout the graphic novel, Spiegelman draws himself as he draws his family and all other Polish Jews -- as a mouse. But on one particularly chilling page, partway through the second volume, that changes.

It's a chilling image of Spiegelman slumped over his desk in despair, sitting on a pile of Jewish bodies, as the various offers of interviews and movie deals hammer down on him. Is it his story to tell? Is he just exploiting other people's suffering? Has he done right by telling his father's story? It's impossible to know, but in this moment, it's clear that Spiegelman thinks not. Where before he has drawn himself as a mouse, now he draws himself wearing a mouse mask, an imposter.

And yet, this image does not come at the end of the story. Whether because he is still conflicted or because he feels it is too late to stop, Spiegelman continues his father's narrative long past this panel, through to his rescue from Auschwitz and his eventual death in 1991.

The Cut Out Girl has a similar moral problem, with the difference that The Cut Out Girl is unaware of it. This is not Bart Van Es's story, or at least not the key part of it. It is Lien's story.

The chapters from van Es's point of view are written in a more comfortable, factual writing style, while Lien's story is written in an attempt to tell things from her perspective, as a young girl. We learn later that Lien's memory is patchy, and that she has no memory of many details she includes. She reads over what he has written and comments that it could have happened that way, but does not say that it was. The whole narrative is filtered through van Es's perspective on things, through the outside research that he does, and his perspective on what he learns. Although Lien tells her story to van Es, he chooses how to tell her story to us.

The Cut Out Girl is an important story, exploring elements about the war in the Netherlands that I, at least, had no idea about. The details are truly frightening. It is horrifying to look at a photograph of 23 people on a beach, and be told near the end of the book that only one of them survived. We’re familiar with this narrative, but it will never lose its horror.

But the fact remains that the author is a white Dutch Oxford professor. He is not even Jewish by heritage, since Lien was adopted into his family for her own protection. Is this his story to tell? What is the significance of the fact that Lien agreed and told it to him, and would not have written it herself?

Obviously, there is significance, in that Lien more than gave her permission for this to be written. But as I read the book, those panels from Maus kept invading my thoughts, and left me with an uncomfortable question for which I believe there is no answer: what is the balance of telling someone's story vs profiting from it, when we're talking about something as traumatic as being Jewish during World War 2?